Recently, I had the opportunity to watch Michael Keaton’s directorial debut, Knox Goes Away. The story of a hitman with an aggressive form of dementia, KGA is dispatch from the heart of loneliness inherent to a solitary life. Keaton's film also sets a sumptuous dramatic banquet of bad decisions.

“Death smiles at us all; all we can do is smile back.” -Marcus Aurelius

What the movie is NOT is a tear-jerker. Knox, (Keaton at his gritty best) takes dementia head-on, as his most terrifying job. If it’s the end, then it will be on Knox' terms and he will settle old mistakes on his way out.

And then his estranged son knocks on his door, bloody and frantic after committing a homocide. Hilarity does not ensue.

Knox Goes Away is a case study of the antihero and the antihero’s appeal. See, most of us do what we can, not necessarily what we should, even less-often what we would really like to do. Mostly we have to suborn our desires, ambitions, and egos to achieve an objective. Which means we have to endure the proverbial slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, (usually 40 hours a week) in order to remain employed or get through a class or to otherwise make a way for ourselves and our family.

The antihero does not move

|

| Now, just hear me out, both are anti-hero stories. |

The anti-hero is wired differently. Some arrive at this juncture after they become disillusioned with social hierarchies and refuse to continue on the hamster wheel, (e.g. Edna, in The Awakening, by Kate Chopin or William, in the film Falling Down). Others have always lived their lives outside the lines of conformity, (think Dr. Lecter or the Addams family). Either way the stage is set for HUGE drama.

|

| “With Hannibal...the bullies get hurt...” |

The hero may be a nonconformist but they’re never outside the lines.

|

| This is Spenser—NEVER a Wahlberg |

Just don’t confuse an antihero for a lazy writer’s get-out-of-a-jam device

|

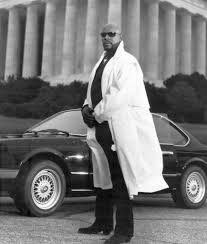

| He is an enforcer not a plot-shoe-horn |

Spenser has a friend named Hawk. We meet him in Promised Land, the fourth Spenser novel, Hawk is a mercenary. Cold, cunning, and completely unencumbered by morality. He often works as an enforcer for loan sharks. That he has killed for money is certainly inferred. That Hawk will kill for convenience is demonstrated.

In The Judas Goat, Hawk says that the one thing he has done that Spenser hasn’t, is to “be black.” It is a telling statement. It imparts a separate reality where black people either reconcile themselves to staying in “their place.” Or live outside deadly lines. Scruples are a fatal weakness.

Spenser can no more understand what it’s like to be a black man in America, than he can kill an unarmed adversary. That kind of bedrock pragmatism doesn’t exist in Spenser’s world. Hawk is the specter of death that Spenser can neither follow nor stay away from.

The same is true of Raymond “Mouse” Alexander, in Walter Mosley’s Easy Rollins books and Carl Franklin's 1995 film. Here, Easy (played by Denzel Washington) is the do-right man but unlike Spenser, Easy is a black man in 1940s and 50s America. He’s driven to live outside the place white America has made for him and not become the very animal American wants to make him out to be.

Mouse (Don Cheadle) is much more practical. Rather than step-and-fetch, Mouse fights—and kills—for his living.

Unfortunately both Hawk and Mouse—compelling as they are—are devices. Both Hawk and Mouse get the do-right men out of plot jams. Parker wrote lean 60K word/200-ish page novelas without an ounce, (excluding recipes) of fat.

So, when Spenser runs afoul of a neighborhood crime boss with an army of goons and no qualms about killing innocents, Spenser has to kill the man or be risk his loved-ones killed by the goons. Spenser realizes this when he has said boss on the ground unarmed and the boss tells him as much.

But Spenser can’t kill an unarmed man and still be the hero. Parker (probably) didn’t want to write another hundred pages of gangland warfare. So Hawk kills the (still unarmed) boss. Problem solved.

Mouse serves a similar function for Easy (and Mosley). In his first foray, Devil in a Blue Dress, Easy has taken the double-crossing bartender, Joppy, in order to find the damsel in deadly danger. It is understood that Easy will not kill Joppy. Easy is the hero.

|

| He dares you to write yourself into another plot corner. |

Yet Mosley could not let a loose thread, (who would definitely tell or sell information of black men gunning down white men at the first opportunity). So Mouse kills Joppy. When Easy, outraged at murder, demands why, Mouse replies, “If you didn’t want him dead, why did you leave him with me?”

Why indeed?

The real antihero, neither device nor sidekick, is a beauty to behold. He (even rarer, she) is beholden to none. They are servants to their own designs.

|

| Not the kind of girl you take home to mother |

Lisbeth Salander is a hacker. She does contract work for an investigative firm. Lisbeth also stalks men who abuse women.

The product of similar abuse, Lisbeth has also been abused by the system that was supposed to protect her. But instead of the path this story normally leads too, (addiction, depravation, and/or death) Lisbeth becomes something other.

Like Mouse, she is physically unable to live within her societal-enforced “place.” Lisbeth creates herself, right down to the fantasy-land name of her apartment. Like Hawk, Lisbeth has a code of personal conduct but is not encumbered by social mores. She is a free person who has trained physically and economically to remain free. At any cost.

Unlike Mouse or Hawk, Lisbeth is not motivated by money, possessions, or status. She wants justice. Most differently from the former, Lisbeth has agency and Larsson elevates her from what first appears to be a new-take sidekick (device?) to the protag of the Millennium series. She most definitely does not do the dirty work so the “hero “ can have clean hands.

“Battlefield doctors decide who lives and dies. It's called triage,” Johns

“They kept calling it murder when I did it,” Riddick

If not already apparent, likeability is not required for the antihero. When we meet Richard B. Riddick, (Vin Diesel) in the film Pitch Black, he is in fetters. An escaped convict, Riddick introduces us to most of the cast, while seemingly in stasis (hibernation for long space voyages). His assessment of each is a predator’s assessment of prey.

|

| Really, stop with the first one. |

Then everything goes pear-shaped, as it does, and Riddick is let off the leash against something that is (again, seemingly) even scarier than he is. The film is a mean, precise master-class in antihero construction. See, Riddick isn’t just the perfect killing machine, he is the ultimate survivor, only too-willing to "triage."

How to get it wrong

Riddick is also a prime example of how to take all of that masterful construction and tie it around a telephone pole like a teen in a sports car. In the follow up film, Chronicles of Riddick, (the title is the first warning) the one-time antihero is a hermit turned messianic savior. The real Richard B. Riddick would’ve died. Either from laughter or embarrassment.

For whatever reason, (someone had incriminating photos, is my guess) there was a third film, Riddick. It tries hard but neither David Twohy, (writer) nor Vin Diesel (star/producer) truly understand the character or why he worked so well the first time.

|

| Crime fiction's most brutal thief |

Donald Westlake, (writing as Richard Stark) crafted perhaps the best antihero of 20th century fiction with his psychopathic heister, Parker. A master thief, Parker is completely amoral and unflinching in his brutality.

But only when money or his life is involved.

Across more than 25 books, Parker steals and kills—but never double crosses a partner, though he kills plenty of partners who try to double cross him.

Like the Spenser novels, Westlake/Stark’s books are lean. More novela than novel. They tend to formula but the entertainment is in the execution. And Parker continues to inform crime writers to this very day for just that exercise of brutal efficiency.

Ultimately, readers/viewers gravitate to the antihero because they do what we, (hero-included) cannot do. They can be ruthless, horrific, even. They will say harsh things in not-nice tones. They show us just how far a hero can fall and often, they are the gray line between protagonist and antagonist.

In testimony before the New York State Senate, Frank Serpico famously said of the NYPD, (and I paraphrase) “Ten-percent are good cops. Ten-percent are bad cops. The remaining eighty-percent want to be good.”

That’s most of us. The antihero doesn’t care. She/he just wants to achieve their objective as cleanly and efficiently as possible. And that clarity of purpose is mesmerizing. It’s why we read/watch Hannibal and Riddick, Lisbeth and Parker.

I own none of the images above. All are used for instructonal/educational purposes as covered by the Fair Use Doctrine.

No comments:

Post a Comment