|

| Oh, SO much promise, so badly bungled. |

Over the weekend, I read an article on the ill-fated Disney television show, The Book of Boba Fett. The story of an bounty hunter first introduced in the movie The Empire Strikes Back, TBoB picks up where we last saw Boba—in the sarlacc that ate him.

The article addressed the character’s arc and why Boba had to change as well as what the writers got wrong yet somehow missed the point. What those writers got wrong—what is all-too commonly wrong in many anti-hero stories—is simple: conviction and fun. The writers lack conviction then they lose the fun of writing an antihero and bleeds it into their story.

An antihero (AH) must have conviction to follow their determination or to survive their circumstances or avenge their wounds. The AH (that acronym can be read a couple of ways and both are correct) is usually way past societal mores and norms by the time the reader/viewer meets them or they get that way real fast. Otherwise, they are not antiheroes—they are dead, or broken, or flotsam of some variety.

Let’s define terms

|

| NOT an antihero. Nope. Not even a little. |

He·ro

/ˈhirō,ˈhērō/

noun

a person who is admired or idealized for courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities—the main character of most stories.

"a war hero"

Similar: champion, savior, man of principle

We all know this do-right man or woman. They populate 90-95% of most stories. Their swell, if a little vanilla. They’re fine, we’re fine, everything’s ~yawn~ fine.

|

| Beheaded a man with a table knife, resumed dinner. |

Vil·lain

/ˈvilən/

noun

The antagonist of most stories, e.g. a bad-guy or bad-woman.

These busters are in EVERY STORY—and not just because they have good agents. Vils and AH may have similar backstories and motivations. The difference is as much “means” as “ends.”

See, whatever else Shakespeare’s Richard III may be, he is ultimately ambitious. Like, “lock children in a tower from which they never emerge” ambitious. There is nothing to root for with RIII. You stick with the play, (or Ian McKellan’s EXCELLENT film) to see him get his.

Also, not our guy/gal.

|

| Now we're talking... |

An·ti·he·ro

/ˈanˌtīˌhērō,ˈan(t)ēˌhērō/

noun

a central character in a story, movie, or drama who lacks conventional heroic attributes.

So, are they one-size-fits-all? Is there a size chart?

Ends, or motivations are at the heart of the antihero dynamic. All heroes are the same. All villains pretty-much are, too. But there are many kinds of antiheroes. So, let's take a tour.

The victim of circumstance:

|

| NOT headed to Hogwarts |

Vito Andolini didn’t choose the thug life, the village boss chose it for him. Mostly by slaughtering all the men in Vito’s family over a grudge. Then, when Vito's mother came calling to beg for Vito’s life, the boss had her murdered as well. Did I mention that Vito was like ten-years-old when HE WITNESSED this all go down?

|

| Who could've imagined that kid turning out like this? |

A new country, new name, new start as a grocery clerk—Vito just wants to support his family and live a quiet life. But when the local Mustache Pete, (gangster) makes it clear that you have to pay for a quiet life in his neighborhood, Vito refuses to bend. The harder Pete pushes, the more entrenched Vito becomes. Then there is the final spark. And, once ignited, Vito’s passion to protect his family turns to a raging inferno of justice for his dead parents and siblings.

“I don’t invite this trouble. It just comes to me.” -Carlito Brigante, After Hours

|

| A Master's Thesis in the Antihero |

So, he immediately pockets the money from a drug-deal gone wrong and buys into a gang-popular nightclub. Only to find out that the streets have a memory longer than any human life. To get away, Carlito must play dangerous games with deadly people.

"The paradise of the rich is made out of the hell of the poor." -Victor Hugo

|

| No quips, here. The book is everything. |

The outraged antihero is one of the most compelling in the form.

Jean Valjean was an honest laborer unable to provide for his family. He steals a loaf of bread and he loses 19 years of his life for it. Upon release from prison, inflamed by injustice, Valjean promptly burgles a church and uses the stolen goods to jumpstart his life.

In Valjean’s story, author Victor Hugo shows us just how close we all are to the one bad day that turns our morals out like empty pockets. He also writes a great treatise on a protagonist driven by outrage as well as an antagonist, Javert, driven, (ridden?) by the same outrage—but of justice/obsession denied.

“…I made a wrong turn and I just kept going…” Bruce Springsteen, Hungry Heart

|

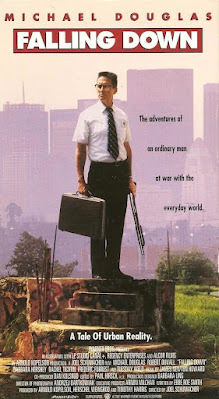

| Who hasn't felt like this on Monday? |

The boil-over rage anti-hero is the one we're most familiar with.

William Foster is a family man. He's a veteran. A skilled technician, who designs components for missiles. He has also been laid off. On the heels of his unemployment, William’s wife left him and filed for divorce. Truly, he’s in a bad place when he’s pushed an inch too far, one-too-many times. See also, Marshal Wyatt Earp, (Tombstone) or John J. Rambo, (First Blood, or book of the same name, avoid the rest like the plague).

“It’s not evil. Just pain, that’s all.” -Sethe, Beloved

Then there is the wounded antihero. They’re not evil. They are hurt and their journey is in defiance of the wounds they suffered and the world that would inflict more injury to bow them or break them. Their crimes are being, their defiance is in their refusal to stop being.

|

| Again, the book is everything. No jokes allowed. |

Sethe is haunted. The specter of slavery lurks in the deep shadows of her freedom. She carries the phantom of barbarity and inhumanity like the “tree” of whip scars across her back. But the greatest haunting that Sethe suffers is the survivor’s terror. The certainty of death escaped, especially after a terrible decision that no mother should have to make.

Sethe’s actions, physical and metaphysical, are both born of horror and survival and crushing guilt.

"She did not know if her gift came from the lord of light or of darkness...she was overcome with almost indescribable relief, as if a huge weight, long carried, had slipped from her shoulders.” Stephen King, Carrie

The same is true of Carrie White. She is a quiet, painfully shy young girl. A bird with a broken wing, Carrie’s mentally-ill-evangelical mother made the first break in Carrie’s spirit. Years of abuse compounded by high school peers did the rest.

When Carrie lashes out, it is not in revenge or even rage. Her action is a desperate, grasping attempt to save her psyche. To live. When Carrie lashes out, it is the net result of years of torment and abuse.

Carrie simply vomits that abuse back on the abusers.

The world said move aside and let me pass and the antihero said, “No. You move.”

Finally, there are the determined antiheroes, driven by righteous retribution. They’re not having a bad day, they’re not victims of circumstance or much of anything else. Those antiheroes, those bad fothermuckers, refuse to suffer the slings and arrows of fate.

Amy Dunne married the man of her dreams, lived in the house of her dreams, and had the life of her dreams. She tells us all of this...eventually. But by the time we meet her, Amy has watched her life whittled away, piece by piece. She leaves her dream life, her dream home, in New York to support her dream husband in Missouri. And then she finds that her all-too real husband is cheating on her.

Rather than go to the mattresses, (divorce attorney). Rather than lament that she was used to anyone who would listen. Rather than start over with nothing. Rather than let life win. Amy decides to die—and wreck her husband’s sh—tuff in the process.

Hilarity does NOT ensue.

|

| Of the two pictured, Riddick is the scarier. |

The vocational antihero is the rarest and most compelling antihero.They follow a true calling. Priests, nuns, and vocational antiheroes, it's not a job, it's a life. The vocational AH is unconcerned with right/wrong. There is only what they want and what they're willing to do to get whatever "it" is.

Richard P. Riddick, (Vin Diesel) is neither shy, nor righteous. Riddick is a killer. It may be during a robbery that goes sideways. It may be to escape the law man for-hire, (Cole Hauser) who gets a payday for chasing Riddick back to prison. It may be against a species looking to eat everyone alive. Doesn’t matter. Riddick is a killer.

Even when he makes a face-turn to save others, it’s never going to be at his own expense. He’s a killer. Not a victim and certainly not a meal.

Where it goes wrong

So, mostly when writers get it wrong—e.g. The Book of Boba Fett, every Riddick movie after Pitch Black—it is in conviction. They roll out a tough guy but then they lose their nerve. Like a compulsion, those writers must write some “hero” into their AH. They don’t trust the audience to appreciate nuance or to root for the not-so-good-not-so-bad guy.

Granted, Boba Fett only had two lines in the original Empire Strikes Back. You can’t build a series of any length on that. But The idea that an orphan who witnessed his father’s beheading, who faced the sarlacc's belly, who gunned down Bib Fortuna to take Jabba’s throne only to become Sheriff Andy Taylor is, to use a technical term, “dumb.”

That is NOT who Boba Felt is.

"Read Marcus Aurelius. Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself?" -Doctor Hannibal Lecter, Silence of the Lambs

Hannibal Lecter remains Lecter. As a physician, he seeks to heal. First, he seeks to heal Special Agent Will Graham but Graham cannot confront with his childhood trauma born of poverty and ignorance. Instead, Graham clads himself in degrees and titles—pretenses that Lecter despises. Lecter wants to be a doctor but Lecter remains Lecter.

Unable to heal Graham, Lecter instead triages Graham and offers him to the Red Dragon as a sacrifice.

Lecter always remains Lecter. Years later, he manipulates circumstances to get himself transferred away from his most deligent guard. Then, when presented with an opportunity to escape, by clumsy and offensive jailers he takes the opportunity and the jailers’ lives. When presented with an opportunity to avenge himself on his tormentor, Lecter "has an old friend for dinner."

Logic is required for conclusions to satisfy

Riddick does NOT become king by his own hand or the Kwisatz Haderach. Just as there is nowhere for Carrie White to go after the cataclysm she throws back on her torturers, there is no happily-ever-after waiting just for William Foster at the end of his long-bad day. Each antihero is locked into their type: victim, wounded, wrathful, or willful, their motivations as much as their means dictate their ending.

|

| You can believe that if you want to... |

Amy Dunne is not a killer. She is a survivor and surviving is not always noble or even pretty. Over the course of her story, we learn that she survived manipulative parents who used Amy like a prop in their profession. We learn that she has survived a stalky-ex-boyfriend. Amy survives worse still in the execution of her plan.

And like Riddick, if things didn’t entirely go “to plan” Amy still survives and, indeed, thrives.

Trust your story. Write your antihero true to their nature. The (most logical) ending will usually present itself. Then you have to trust the reader/viewer to understand who they’ve been hanging out with.

It’s a risk. That risk has paid off for the writers brave enough to do the work and let their AH stand on their own, (neither hero, nor villain but shades of both) following their own path. It’s just that simple and it’s just that hard.

I own none of the photos above. All are used for educational/instructional purposes as covered by the Fair Use Doctrine.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment